Child’s play: Individual character and freedom of design

A recent decision by the Board of Appeal of the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), in a dispute over educational toys for children, illustrates the limited degree of freedom for designers under design law. Bente van den Eijnden sets out the implications of the ruling.

Design law enables brand owners to protect the appearance of a product (or part of it), such as colour, shape or texture/material. As such, it can be very interesting for companies that market products with unique designs. It enables them to act against the production or sale of infringing products, either on the basis of an unregistered design right (which has a maximum protection term of three years) or a registered design (which protects for up to 25 years).

To be eligible for design protection, a product’s design must meet certain criteria; in particular, it must be ‘new’ and have an ‘individual character’. The need for novelty in this instance means that no identical drawing or model must have been previously made available to the public. Satisfying the criterion of individual character is slightly more complicated.

To establish ‘individual character’, examiners will first assess whether a so-called ‘informed user’ would distinguish between the design and a similar product. In other words, if the informed user would consider that the product design creates the same overall impression as a design that has been previously made available to the public, it may not possess sufficient ‘individual character’ to be eligible for design protection.

In addition, the nature of the product and the degree of freedom of the designer must be taken into account. Where elements of a product are technically determined, the designer’s creativity will be limited when developing the drawing or model. The less freedom the designer has, the lower the bar for establishing individual character.

A recent decision by EUIPO’s Board of Appeal on educational toys for children (Model Creative Design Ideas v Octoplay) illustrates the question of a designer's freedom under design law.

Background to the ruling

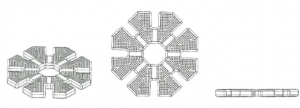

British company Creative Design Ideas Ltd registered a European design right (pictured below left) for educational toys in October 2014. It was annulled in 2017 after Shine Shimizu, a Japanese company, filed an invalidity action on the grounds of lack of individual character.

To support its case, Shine Shimizu submitted as evidence an image of a model known as the ‘Octoplay’ (pictured below right) , which had been on sale to the public since 2008. Although it conceded that the informed user would be able to see the differences between the two designs, EUIPO’s Invalidity Division found the overall impression of the two designs to be the same, and annulled the 2014 right. Creative Design Ideas lodged an appeal, arguing that that EUIPO’s Invalidity Division had not taken the degree of freedom of the designer sufficiently into account.

, which had been on sale to the public since 2008. Although it conceded that the informed user would be able to see the differences between the two designs, EUIPO’s Invalidity Division found the overall impression of the two designs to be the same, and annulled the 2014 right. Creative Design Ideas lodged an appeal, arguing that that EUIPO’s Invalidity Division had not taken the degree of freedom of the designer sufficiently into account.

On appeal

As set out above, if the freedom of a designer in the development of the product is limited, the small differences between the designs will be sufficient to create a different overall impression for the informed user.

In this case, the freedom of the designer is limited, as the type of toy requires that the different parts must be connectable via notches. However, that does not necessarily mean (as Creative Design Ideas argued) that the toy must be formed of octagonal shapes. The parts would be connectable whatever their shape; indeed, the educational purpose of such toys would arguably be higher if new types were created giving consumers more choice.

As a result, EUIPO’s Invalidity Division decided that the designer had sufficient freedom that the small differences between the designs is not enough to create a different overall impression on the informed user, and dismissed the appeal.

To find out more about design protection, please visit the pages on our website, speak to your Novagraaf attorney or contact us below.

Bente van den Eijnden works in Novagraaf’s Competence Centre. She is based in Amsterdam.