- Trademarks & Designs

- Trademarks & Designs

- Strategy & managementUnlock the potential of your brand portfolio

- SearchingScreening and clearance search with smart pre-selection

- RegistrationTailored support to maximise your brand potential

- WatchingMonitor rights efficiently and cost-effectively worldwide

- Monitoring & prosecutionProtect and enforce rights on- and off-line

- Renewals & recordalsFlexible renewal and recordal services

- Strategy & management

- IP consultingBrand development, audits, licensing, M&A, valuation/monetisation, contract management and more

- IP consulting

- Patents

- Solutions

- Trademarks & Designs

- Trademarks & Designs

- Strategy & managementUnlock the potential of your brand portfolio

- SearchingScreening and clearance search with smart pre-selection

- RegistrationTailored support to maximise your brand potential

- WatchingMonitor rights efficiently and cost-effectively worldwide

- Monitoring & prosecutionProtect and enforce rights on- and off-line

- Renewals & recordalsFlexible renewal and recordal services

- Strategy & management

- IP consultingBrand development, audits, licensing, M&A, valuation/monetisation, contract management and more

- IP consulting

- Patents

- Solutions

- Contact

- About us

- About us

- About usProud to support iconic brands and innovative organisations worldwide

- Mission & visionDiscover how we are redefining IP management through dynamic, strategic and personalised services

- MilestonesExplore our history from our founding 135+ years ago to the present day

- Our offices18 offices and unique network of specialists delivers local expertise on a global scale

- Social responsibilityWe strive to positively impact the environment and the global community in which we work and live

- GovernanceInnovation, client focus and a passion for IP. Meet our management team

- About us

- Careers

- Log in

- About us

- About us

- About usProud to support iconic brands and innovative organisations worldwide

- Mission & visionDiscover how we are redefining IP management through dynamic, strategic and personalised services

- MilestonesExplore our history from our founding 135+ years ago to the present day

- Our offices18 offices and unique network of specialists delivers local expertise on a global scale

- Social responsibilityWe strive to positively impact the environment and the global community in which we work and live

- GovernanceInnovation, client focus and a passion for IP. Meet our management team

- About us

- Careers

- Log in

EU General Court rules in latest Rubik’s Cube case

After its patent rights expired, the owners of the iconic Rubik’s Cube attempted to use trademark registrations to extend its protection. After decades of disputes, its black and white trademark and now its colour trademark have been found invalid, as Volha Parfenchyk explains.

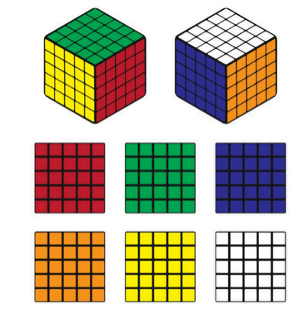

Invented in 1974, the famous Rubik's Cube was protected by a patent for 20 years. When that patent expired, Seven Towns Ltd, the company that held the IP rights to the invention, attempted to extend its protection through trademark law. The company registered several trademarks, including the three-dimensional (3D) EU trademark 000162784 and EU trademark 009976788, which depict the cube in black and white and in colour, respectively.

However, after decades of legal debate, both trademarks were declared invalid by the highest EU judicial bodies. The black and white trademark was declared invalid in 2019, and now, in a recent ruling, the colour trademark has been found invalid by the EU General Court.

Background to the Rubik’s Cube case

The contested mark was registered on 5 March 2012, as a 3D or shape mark (pictured below, left).

On January 25, 2013, the Greek company Verdes Innovations SA filed an application at the EUIPO for the mark to be declared invalid. The ground relied on in support of the application for a declaration of invalidity was set out, among others, in Article 7 of Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community Trademark (CTMR), repealed and replaced by Regulation 2017/1001 on the European Union Trademark (EUTMR). Article 7 of both regulations lays out absolute grounds for refusal or invalidity of trademarks. In particular, according to Article 7(1)(e)(ii): “signs which consist exclusively of the shape, or another characteristic, of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result” are excluded from protection.

On January 25, 2013, the Greek company Verdes Innovations SA filed an application at the EUIPO for the mark to be declared invalid. The ground relied on in support of the application for a declaration of invalidity was set out, among others, in Article 7 of Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community Trademark (CTMR), repealed and replaced by Regulation 2017/1001 on the European Union Trademark (EUTMR). Article 7 of both regulations lays out absolute grounds for refusal or invalidity of trademarks. In particular, according to Article 7(1)(e)(ii): “signs which consist exclusively of the shape, or another characteristic, of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result” are excluded from protection.

The EUIPO Cancellation Division suspended the proceedings pending a final decision on the application for cancellation of the 3D EU trademark depicting a black-and-white Rubik's Cube (the proceedings discussed in our previous article). After the final decision was issued, the ongoing cancellation proceedings were resumed.

Both the EUIPO Cancellation Division and the EUIPO Board of Appeal partially upheld the application for a declaration of invalidity of the contested mark in respect of the goods in class 28. In particular, the EUIPO Board of Appeal ruled, first, that the colours of the squares on each side of the cube were an essential characteristic of the trademark and formed an integral part of the shape of that mark. Second, it ruled that the combination of these different colours was necessary to obtain a technical result. Hence, it concluded that the mark had been registered contrary to the provisions of Article 7(1)(e)(ii) of the CTMR as it was a sign which consists exclusively of the shape which is necessary to obtain a technical result.

Spin Master Toys UK Ltd, the current holder of the IP rights to the Rubik's Cube, filed an appeal with the General Court of the EU.

The ruling of the EU General Court

The EU General Court passed its ruling on 9 July 2025. It agreed with the EUIPO Cancellation Division and the Boards of Appeal and dismissed the appeal, declaring the Rubik’s Cube trademark invalid.

- Functional character of the essential characteristics of the shape

Referring to its conclusions in the previous rulings, the EU General Court stated that for the correct resolution of the dispute, and the correct application of Article 7(1)(e)(ii), it was crucial to first establish the essential characteristics of the shape. The aim of identifying the essential characteristics of the shape is to examine whether the shape as a whole has a functional or technical purpose. If all essential characteristics of the shape are functional and necessary to obtain a technical result, then the shape as a whole is seen as having a functional purpose and, therefore, cannot be registered as a trademark.

What does this provision imply for the elements of a shape that have aesthetic value? This question was of great importance in this case as the aesthetic value of the shape – namely, the fact that different sides of the cube had different colours – was one of the main features distinguishing this trademark registration from the one that was declared invalid in the proceedings around the black and white cube. This was also one of the main arguments that the trademark holder used in the current proceedings.

The Court ruled that the aesthetic value of a particular characteristic of the shape can indeed be relevant for answering the question of whether the shape at hand can enjoy trademark protection, but only when this characteristic of the shape is essential. The presence of minor and insignificant aesthetic features which do not constitute essential characteristics of the shape is irrelevant for deciding on the applicability of Article 7(1)(e) (ii).

Further, in case a particular characteristic of the shape is essential, the shape can enjoy trademark protection if this characteristic is merely aesthetic and does not perform any technical function. If it does perform a technical function, then the shape cannot be protected by trademark law, even though this characteristic is also aesthetic and adds to the decorative value of the shape. In short, if the shape has an element that is both essential and merely decorative (non-functional), then it can be protected as a trademark.

- Different colours as a non-essential characteristic of the shape

The six specific colours assigned to the different sides of the cube by the trademark holder and their arrangement were, according to the Court, a minor arbitrary element, not constituting an essential characteristic of the shape. Because it was not essential, the fact that it was not functional (the trademark holder chose and applied these colours on the different sides of the cube following personal aesthetic considerations) was thus irrelevant.

In contrast, the essential characteristics of the cube are, first, the cube shape, second, the grid structure and, third, the very fact that the faces of the cube are differentiated from each other by means of a colour which produces a contrasting effect. Regarding the third characteristic, namely, the differentiation of the sides of a cube by means of colour, the Court stated that it was not the same as the application of specific colours to each side of the cube and their arrangement, referred to by the trademark holder. The trademark holder indeed chose and applied different colours to the sides of the cube following its individual aesthetic preferences. However, the specific choice of colours was not of major importance and thus not essential, unlike the decision to differentiate the sides of the cube by means of a contrasting effect (the decision, which was also functional, as shall be discussed later) and therefore irrelevant for the resolution of the dispute.

- Different colours as an integral part of the shape

Spin Master also put forward that the six colours and their specific arrangement on the sides of the cube do not form an integral part of the ‘shape’ within the meaning of Article 7(1)(e)(ii). As a result, this provision does not apply to the contested mark, as it does not consist exclusively of the shape of the good.

The General Court also refuted this argument. The Court emphasised that the contested mark was filed and registered as a 3D mark or shape mark, and not as a two-dimensional mark (2D) or pattern mark applied to the surfaces of a shape, nor as a position mark placed on or affixed to a shape, nor as a colour mark per se. Hence, all characteristics of the shape, including the use of colours for the purpose of creating a contrasting effect, are inherent in and inseparable from the shape represented. Because they merge with shape, they cannot be examined independently of it. Therefore, the Board of Appeal correctly applied Article 7(1)(e)(ii) to the contested sign as exclusively consisting of a shape within the meaning of this article.

- Different colours as a functional characteristic of the shape

The trademark holder further stated that the specific colours and their specific arrangement were not necessary to obtain a technical result. While it was necessary that the six sides of the cube were to be differentiated, the way in which this is achieved is not a technical question, but merely an aesthetic one. There exist multiple design possibilities in respect of the surface design of the shape, and the choice for a design is not limited by technical considerations.

The Court refuted this argument as well. It stated that even if it was true that the intended technical result can be achieved by an infinite number of surface designs, it did not change the fact that the choice of a design possibility was also functional. According to the Court, there exists a causal link between the choice of a design of the surface and the technical result, that is, whether the surface design makes it possible to distinguish the faces of the cube by means of a contrasting effect. Hence, and as mentioned above, this capacity of the different colours to differentiate the sides of the cube was both an essential and functional characteristic of the shape. The fact that it also had an aesthetic value and that was chosen by the trademark holder following its aesthetic considerations was irrelevant.

- Applicability of Article 7(1)(e)(ii) to ‘jigsaw puzzles’

Finally, the trademark holder argued that the EUIPO wrongly applied its decision to “jigsaw puzzles” in class 28 since jigsaw puzzles are inherently two-dimensional. The Court refuted this argument as well. According to it, the definition of “jigsaw puzzles” could be interpreted as meaning a 2D ‘picture’ and ‘jigsaw puzzles’ in volume (i.e., 3D). Regarding which of the two interpretations should apply in this case, the Court stated that it should not be interpreted in such a way that it includes only, for the benefit of the trademark holder, 2D ‘jigsaw puzzles’, which would allow them to refute the applicability of Article 7(1)(e)(ii) to these goods. The trademark holder should not gain from the infringement of its obligation to draw up the list of goods with clarity and precision. Hence, ‘jigsaw puzzles’ should also be interpreted as meaning 3D puzzles, justifying the refusal of the sign to the entire class 28.

Implications of the Rubik’s Cube case

Whereas the holder of IP rights on Rubik’s Cube has indeed lost its important trademarks, it is important to remember that the name and logo of the Rubik’s Cube remain protected as registered trademarks. In addition, in the Netherlands, the combination of the cube’s width, colours, and the thickness of the grid is protected under copyright law. Finally, as Spin Master can still appeal the decision of the General Court at the Court of Justice of the EU, it remains to be seen how broad the IP rights protection of the famous invention shall be.

To find out more about trademark protection in the EU, speak to your Novagraaf attorney or contact us below.

Volha Parfenchyk works in Novagraaf’s Knowledge Management department. She is based in Amsterdam.