- Trademarks & Designs

- Trademarks & Designs

- Strategy & managementUnlock the potential of your brand portfolio

- SearchingScreening and clearance search with smart pre-selection

- RegistrationTailored support to maximise your brand potential

- WatchingMonitor rights efficiently and cost-effectively worldwide

- Monitoring & prosecutionProtect and enforce rights on- and off-line

- Renewals & recordalsFlexible renewal and recordal services

- Strategy & management

- IP consultingBrand development, audits, licensing, M&A, valuation/monetisation, contract management and more

- IP consulting

- Patents

- Solutions

- Trademarks & Designs

- Trademarks & Designs

- Strategy & managementUnlock the potential of your brand portfolio

- SearchingScreening and clearance search with smart pre-selection

- RegistrationTailored support to maximise your brand potential

- WatchingMonitor rights efficiently and cost-effectively worldwide

- Monitoring & prosecutionProtect and enforce rights on- and off-line

- Renewals & recordalsFlexible renewal and recordal services

- Strategy & management

- IP consultingBrand development, audits, licensing, M&A, valuation/monetisation, contract management and more

- IP consulting

- Patents

- Solutions

- Contact

- About us

- About us

- About usProud to support iconic brands and innovative organisations worldwide

- Mission & visionDiscover how we are redefining IP management through dynamic, strategic and personalised services

- MilestonesExplore our history from our founding 135+ years ago to the present day

- Our offices18 offices and unique network of specialists delivers local expertise on a global scale

- Social responsibilityWe strive to positively impact the environment and the global community in which we work and live

- GovernanceInnovation, client focus and a passion for IP. Meet our management team

- About us

- Careers

- Log in

- About us

- About us

- About usProud to support iconic brands and innovative organisations worldwide

- Mission & visionDiscover how we are redefining IP management through dynamic, strategic and personalised services

- MilestonesExplore our history from our founding 135+ years ago to the present day

- Our offices18 offices and unique network of specialists delivers local expertise on a global scale

- Social responsibilityWe strive to positively impact the environment and the global community in which we work and live

- GovernanceInnovation, client focus and a passion for IP. Meet our management team

- About us

- Careers

- Log in

G 1/23: Does a technological black box constitute prior art in European patent law?

Can a product which is marketed but not reproducible/analysable be considered prior art? This is the question at the heart of the decision in G 1/23, says Philippe Vigand. He explains the implications of the Enlarged Board of Appeal’s findings.

The question in G 1/23 concerned the interpretation of Article 54(2) of the European Patent Convention (EPC), which defines prior art as anything which has been made available to the public, by written/oral description, use or otherwise, before the filing date.

In T 438/19, a debate arose: can a product which is marketed but not reproducible/analysable be considered prior art?

In its decision of 2 July 2025, the Enlarged Board of Appeal gave the following answers:

"A product placed on the market before the filing date of a European patent application cannot be excluded from the state of the art within the meaning of Article 54(2) EPC solely on the ground that its composition or internal structure could not be analysed and reproduced by a person skilled in the art before that date [...] Technical information relating to such a product which was made available to the public before the filing date forms part of the state of the art within the meaning of Article 54(2) EPC, irrespective of whether the skilled person could analyse and reproduce the product and its composition or internal structure before that date.”

The on-sale bar: Highlights of the Grand Chamber's arguments

- 1. Criticism of the criterion of "reproducibility" as set out in G 1/92

The Board rejects the two traditional interpretations from G 1/92:

- (i) That the entire product is excluded from the state of the art if it is not reproducible.

- (ii) That only its composition is excluded.

It considers that these two readings lead to legal and technical absurdities, such as making any non-reproducible product invisible under patent law, which is unrealistic and contrary to technical practice.

- 2. The product placed on the market is prior art

A product that is physically accessible to the public (even if it is not reproducible) belongs to the state of the art.

This principle is based on the idea that a professional in the field ("person skilled in the art") can use this product, even without being able to recreate it by other means.

The decision stresses that it would be absurd to claim that such a product "does not exist" legally when it is commercially available and technically used.

- 3. Logical argument: every product relies on other non-reproducible products

To reject non-reproducible products from the prior art would be to exclude almost all materials, since no product can be recreated from scratch.

This would render Article 54(2) EPC meaningless and paralyse the examination of novelty and inventive step.

- 4. Distinction between analysis and reproduction

The capacity for analysis (determining the accessible properties) is sufficient for these properties to be opposable.

Reproducibility is not required: The professional does not need to know how to remake the product for it or its properties to be considered as prior art.

- 5. Reflection on the "undue burden"

The concept of "undue burden" is rejected: the Enlarged Board considers that only analysis is relevant, as long as it is technically possible with standard means.

The difficulty or cost of analysis does not exclude technical information obtained from the prior art.

- 6. Disappearance or modification of the product

The criterion of analysis and reproduction introduced by G 1/92 is interpreted more broadly: the possibility for an expert to physically obtain the commercial product is already sufficient to satisfy this criterion.

The fact that the product becomes unavailable or subsequently modified does not retroactively alter its prior art.

- 7. Inventive step: "legally present" but "technically silent"

A non-reproducible product is prior art if it has been made available to the public.

However, it is only enforceable on the basis of inventive step to the extent that a professional could have derived some relevant technical information from it.

In other words, it is "legally present" but "technically silent" for the assessment of the obvious, if no useful information is accessible.

- 8. Conclusion reached by the Enlarged Board

A product placed on the market belongs to the state of the art, even if its composition or internal structure cannot be analysed or reproduced, as long as its properties are publicly available through its use or through available documentation.

Practical consequences of the decision

- A product sold or made available is now equivalent to prior art, even if it cannot be analysed or reproduced.

- Any technical distribution (technical sheet, advertisement, etc.) is enforceable as prior art.

- For Europe, applicants must patent their inventions before any commercialisation or public disclosure, under penalty of losing the novelty.

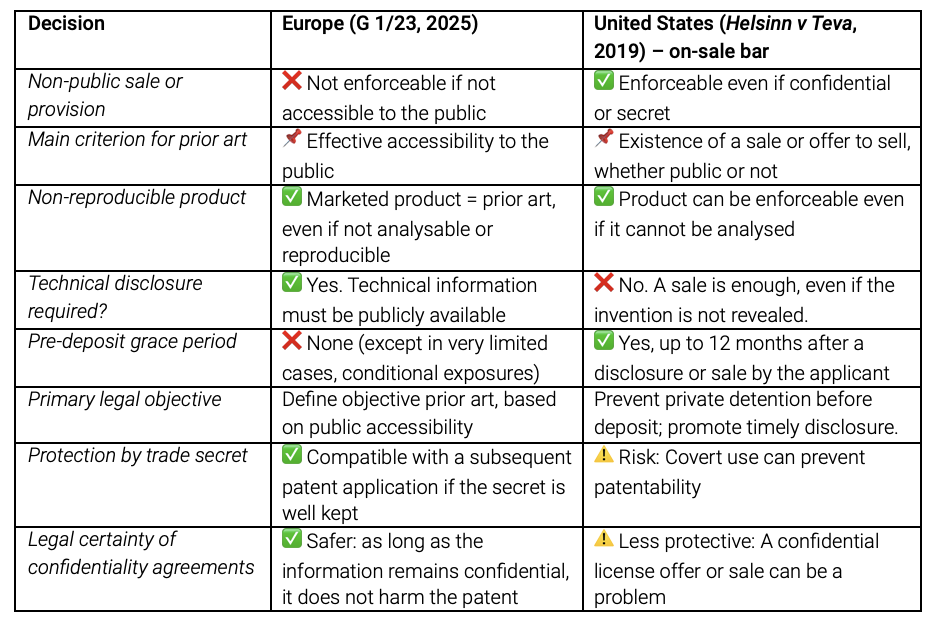

Comparison with the United States on-sale bar

Key interpretation of the on-sale bar/technological black box

- In the United States, with the "on-sale bar" decision, the focus is on the date of commercialisation, regardless of whether the invention is secret or not. It is better to patent quickly, or at the latest within a year, in the case of commercial use of the invention.

- In Europe, there is no technological black box but the principle of transparency prevails: only what is actually accessible to the public can be opposed, even if it cannot be reproduced. This reinforces the strategic value of industrial secrecy if one chooses not to patent, at least for the time being.

To find out more about the implications of the G 1/23 and on-sale bar patent rulings for your organisation, speak to your Novagraaf attorney or contact us below.

Philippe Vigand is Managing Director, Patents and a European, French and Swiss Patent Attorney based at Novagraaf in Switzerland.